Decoding the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine: The discovery of regulatory T cells, the “brakes” of immune responses

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to three scientists: Dr. Shimon Sakaguchi (Specially Appointed Professor, Osaka University, Japan), Dr. Mary Brunkow (Senior Program Manager, Institute for Systems Biology, USA), and Dr. Fred Ramsdell (Scientific Advisor, Sonoma Biotherapeutics, USA). The prize recognized their “discoveries concerning peripheral immune tolerance.” In this article, Professor Noriko Komatsu (Institute of Integrated Research, Institute of Science Tokyo) explains their achievements.

Please tell us the reason for the award and an overview of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

Komatsu Every day, we are exposed to enormous numbers of pathogens such as viruses and bacteria. What protects our bodies from them is the “immune system.” In the immune system, it is also important not to overreact to foreign substances such as pollen and mites, and not to attack our own body. Otherwise, we may develop allergies due to excessive responses to foreign substances, or autoimmune diseases due to attacks on ourselves.

One of the key players in the immune system is a type of lymphocyte called the “T cell.” T cell precursors are produced in the bone marrow and then mature T cells are generated in an organ called the thymus. Mature T cells enter the bloodstream and patrol the body. Among these T cells, which serve as the “accelerator” of the immune system, are “cytotoxic T cells” and “helper T cells.” Killer T cells attack cells infected with pathogens, while helper T cells convey information about pathogens to other immune cells and instruct them to act.

Dr. Sakaguchi, one of this year’s laureates, clarified the existence of regulatory T (Treg) cells, which function as the immune system’s “brakes,” preventing the immune system from becoming overactive and damaging the body itself, thereby avoiding autoimmune diseases. In immunology, there has long been a major question: “Why do autoimmune diseases develop?” One answer to this question is known as “central immune tolerance.” Immune tolerance refers to the function of suppressing immune responses against the self, and central immune tolerance is a system in the thymus that eliminates T cells that could potentially attack self-tissues. This helps prevent autoimmune diseases.

However, central immune tolerance is not a perfect system. The system that protects the body in peripheral tissues so that T cells that escape this system and flow out into peripheral tissues do not attack self-tissues and cause disease is called “peripheral immune tolerance.” Yet, for many years, it remained a mystery how this “tolerance” is achieved. In response, Dr. Sakaguchi and colleagues discovered Treg cells that suppress immune responses, which for the first time revealed the validity of the concept of peripheral immune tolerance and also uncovered part of its concrete mechanism. This achievement was recognized and led to the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Please tell us how the discovery of Treg cells was made

Komatsu About 50 years ago, during his graduate studies at Kyoto University, Dr. Sakaguchi became interested in experimental results reported in 1969 and 1976 by the research team of Dr. Yasuaki Nishizuka (Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute, Japan). The findings were that “if the thymus is removed from mice on the third day after birth, those mice develop autoimmune disease when they become adults.” Dr. Sakaguchi therefore left the Kyoto University graduate program in 1977, became a researcher at this institute, and began his research. In the early 1980s, he discovered that autoimmune disease could be prevented by transplanting mature T cells taken from healthy mice into mice whose thymus had been removed on the third day after birth.

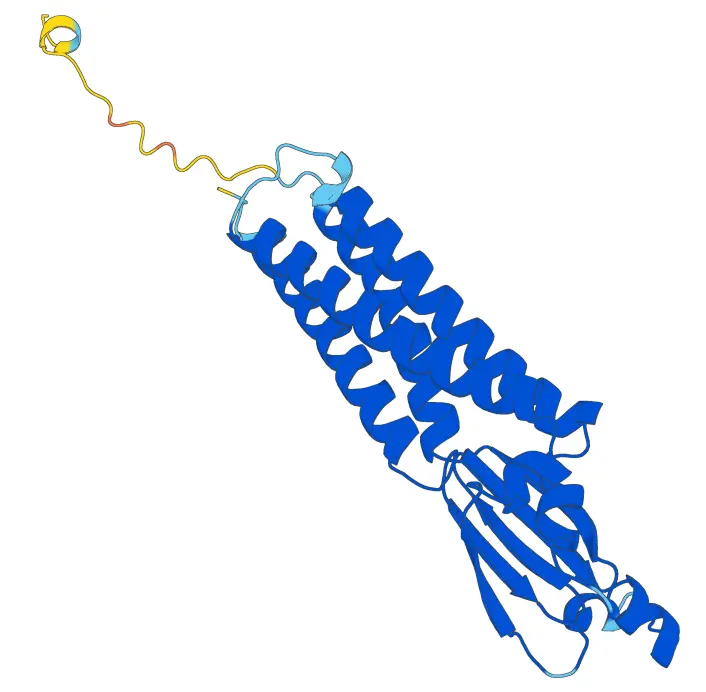

Based on these results, Dr. Sakaguchi proposed the hypothesis that there exist T cells that suppress immune responses. Then, over about 10 years, he experimentally identified a new type of T cell bearing two proteins, CD4 and CD25, that suppresses autoimmune disease in mice. These T cells are Treg cells, and part of the long-standing mystery of peripheral immune tolerance was experimentally demonstrated.

Meanwhile, Dr. Brunkow and Dr. Ramsdell made a major discovery concerning a gene essential for the establishment of self-tolerance. First, during the “Manhattan Project,” the U.S. atomic bomb development program, animal experiments were conducted to investigate the effects of radiation. In the course of these experiments, mice that developed autoimmune disease were discovered by chance. In 2001, it was Dr. Brunkow and Dr. Ramsdell who identified the gene responsible for autoimmune disease in these mice.

The causal gene is called “Foxp3,” and Dr. Brunkow also discovered that mutations in this gene in humans cause an autoimmune disease called “IPEX.” Furthermore, Dr. Sakaguchi and Dr. Shohei Hori (Professor, The University of Tokyo, Japan) were the first to demonstrate—prevailing in intense global competition—that Foxp3 is an indispensable gene for the phenotype and suppressive function of Treg cells. The paper reporting this experimental research has now become a landmark in immunology.

In other words, Dr. Sakaguchi first experimentally proved the existence of Treg cells, and then Dr. Brunkow and Dr. Ramsdell identified Foxp3 as the causal gene of the autoimmune disease IPEX. As an important discovery linking these two findings, Dr. Sakaguchi proved that Foxp3 is an essential gene for Treg cells.

What kind of research is being conducted in Professor Komatsu’s laboratory?

Komatsu I am working on research to elucidate the pathology of autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis is one of the autoimmune diseases with the highest prevalence, and its main symptoms are joint inflammation and bone destruction. However, many aspects of the mechanism of onset remain unclear, and the details are not yet fully understood. On the other hand, in recent years, many studies have increasingly supported the idea that abnormalities in Treg cells may be one of the causes of rheumatoid arthritis.

To date, I have shown that T cells considered “beneficial,” which express Foxp3, can transform into “highly harmful” cells by losing Foxp3 expression, thereby causing joint inflammation and bone destruction. I have also clarified that interactions between T cells and non-immune cells that make up the body are closely involved in this phenomenon. Through this research process, I aim to elucidate the mechanisms by which autoimmune diseases occur and to connect this knowledge to treatment, focusing on communication between immune cells and non-immune cells.

In addition, at Science Tokyo, research on Treg cells is actively progressing. Examples include elucidating the molecular mechanisms of interactions between tumor cells and Treg cells in colorectal carcinogenesis, and the discovery that leukemia cells acquire the ability to induce Treg cells in lineage-switch relapse of leukemia. These studies are expected to lead to the development of new preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic approaches for cancer.

Please tell us about future developments

Komatsu The immune system is known to be closely related to autoimmune diseases, allergies, transplant rejection, and cancer cells. Properly controlling Treg cells is expected to lead to the treatment and prevention of these conditions. Therefore, research on medical applications of Treg cells is now advancing worldwide. Expectations are growing ever higher for further understanding of the immune system based on Treg cells and for their medical applications.

* This article is based on the presentation given at Science Tokyo Nobel Prize Lecture, held online on Wednesday, November 26, 2025.

Research news at Science Tokyo linked to Professor Komatsu and the Nobel Prize

Science Tokyo organizations conducting related research

Decoding the Nobel Prize series

Contact

Research Support Service Desk