What is a “seesaw protein” that switches functions by changing shape?

An artificial protein that “transforms” between two faces—glowing and working

What the research is about

Do you remember playing on a seesaw in the park as a child? When one side goes up, the other side goes down. Inspired by this simple mechanism, researchers asked an intriguing question: Could a single molecule switch between two different roles, just like a seesaw? This idea led to the creation of a new type of artificial protein called the “seesaw protein.”

Proteins are chains of amino acids that fold into specific three-dimensional shapes, and these shapes determine how proteins work. According to Anfinsen’s dogma, proposed in the mid-20th century, a given amino acid sequence folds into one unique structure. However, later studies revealed exceptions, such as “chameleon sequences,” which can adopt different structures depending on their environment. In nature, some proteins are also known to change their structure—and function—according to their role.

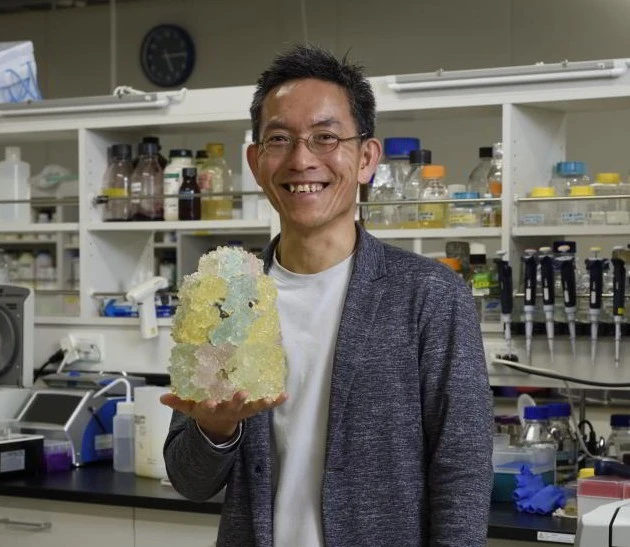

Taking inspiration from these findings, a research team led by Professor Hideki Taguchi at Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo) set out to explore whether a single protein could be designed to switch between two completely different functions. This question became the starting point of their research.

Why this matters

The team successfully created a new artificial protein, which they named the seesaw protein. It combines two very different types of proteins into a single, structurally overlapping protein: a fluorescent protein, which emits light and is easy to observe, and an enzyme, which plays an essential role in biological processes.

The key feature of the seesaw protein is that only one function is active at a time. When the protein is glowing, it does not act as an enzyme; when it works as an enzyme, it does not glow. The two states never appear simultaneously.

Remarkably, this switching can be precisely controlled by small changes, such as replacing just one amino acid, binding a drug molecule, or adjusting conditions like pH or salt concentration. This design truly mirrors a seesaw: when one side rises, the other must fall. The research team also succeeded in directly observing the moment when a single protein molecule changes its shape, using high-speed atomic force microscopy—a powerful technique that allows visualization at the single-molecule level.

What’s next

This achievement opens the door to next-generation artificial proteins whose functions can be switched in response to external stimuli. Possible applications include medical sensors, drug delivery systems, and synthetic biology.

In fact, the design of artificial proteins is attracting worldwide attention. It was highlighted as a major theme in the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry (see the related article “Decoding the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry”), where designed proteins played a central role.

In addition, because light emission and enzyme activity can be used as markers inside cells, seesaw proteins may enable evolution experiments guided by design, leading to a new field of molecular engineering that designs evolution itself. In the future, it may even be possible to create proteins from scratch that switch between entirely new functions not found in nature.

Comment from the researcher

In simple terms, my long-term research challenges one of the fundamental assumptions of protein science—Anfinsen’s dogma—in order to uncover new aspects of the protein world. By successfully designing a ‘metamorphic’ protein that can adopt multiple structures from a single amino acid sequence, we believe we have expanded the potential of what proteins can do.

Naming this protein a ‘seesaw’ has also helped convey the excitement of protein research beyond specialists, reaching a much broader audience. This research was carried out together with Researcher Tatsuya Nojima and Toma Ikeda, a second-year doctoral student at the School of Life Science and Technology. Ikeda received the Outstanding Young Investigator Award at the 2025 Annual Meeting of the Protein Science Society of Japan. Since it is rare for a student to receive this award while still enrolled, we believe it reflects the strong impact of this research.

(Hideki Taguchi, Professor, Cell Biology Center, Institute of Integrated Research Institute, Institute of Science Tokyo)

Dive deeper

Contact

- Remarks

- Research Support Service Desk