A new “crystalline sponge” for drug discovery: APF-80 illuminates materials design

Harnessing the strengths of MOFs spotlighted by the Nobel Prize—while overcoming their key limitations

What the research is about

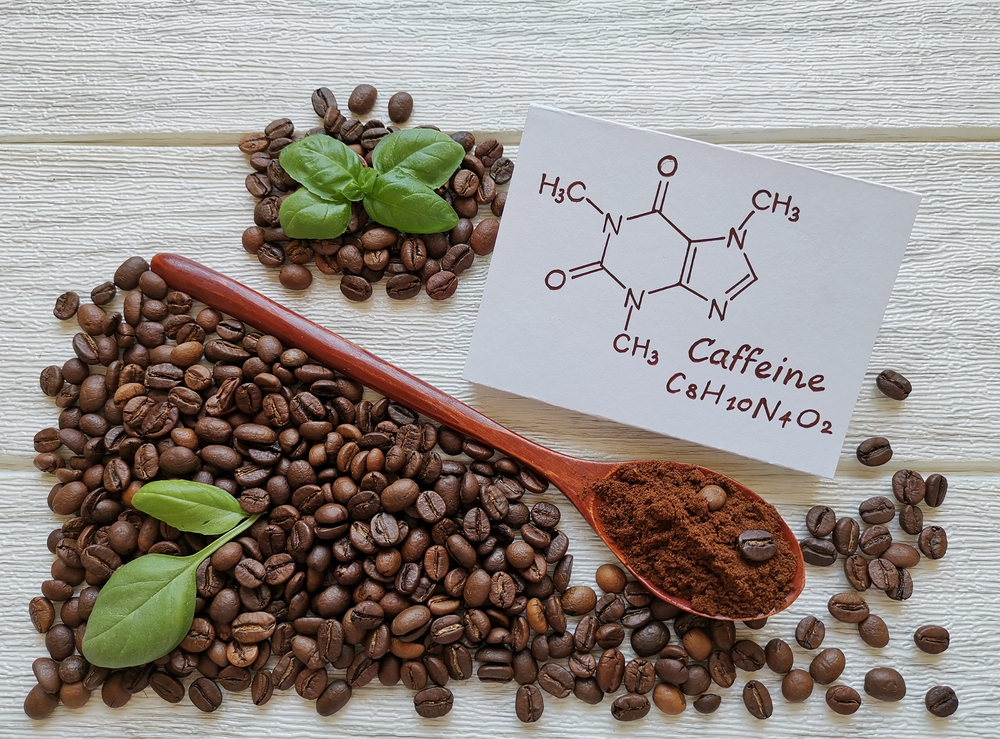

After drinking coffee, you may feel mentally refreshed. Spices in curry can make your body feel pleasantly warm. Behind such reactions, naturally occurring compounds are at work inside our bodies. Many natural compounds that act on the human body provide active ingredients for medicines or clues for developing them, and they play a crucial role in pharmaceutical research.

Among these natural compounds, many molecules classified as alkaloids—such as caffeine, nicotine, and morphine—are highly complex, and often available only in very small quantities. To understand how alkaloids act in the body, it is important to grow large crystals of the molecules and determine their structures by X-ray diffraction. However, for molecules like alkaloids, crystal growth itself is difficult.

A method that addresses this challenge is the “crystalline sponge method.” In this approach, molecules are absorbed into a crystalline material with regularly arranged, sponge-like pores, and researchers observe how the molecules are fixed within those pores. The “crystalline sponge” used for this purpose is a metal–organic framework (MOF), a class of materials recognized by the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2025. Because MOFs have orderly, lattice-like pores, they are well suited to the crystalline sponge method. However, a longstanding drawback has been that when highly reactive molecules such as alkaloids are introduced, the MOF itself can collapse.

Why this matters

A research team led by Professor Masaki Kawano and Assistant Professor Yuki Wada at Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo) has created APF-80, a new MOF that resolves the long-standing issue of MOF fragility, which has hindered wider use of the crystalline sponge method.

APF-80 is a MOF composed of metal ions (cobalt) and organic molecules. The team identified and incorporated an organic molecule that strengthens the crystal itself more effectively than in conventional MOFs. In addition, they introduced a design that prevents the crystal from degrading by shielding the parts of the structure where reactions are likely to occur, even when highly reactive molecules are introduced. They also implemented a structural design in which the absorbed molecules cooperate with the MOF and function like an adhesive. Through these improvements, molecules no longer wobble inside the crystal; instead, they become firmly immobilized—as if they hold perfectly still just before a photograph is taken.

Using this approach, the team was able to visualize the three-dimensional structures of a wide range of compounds—including caffeine, nicotine, and omeprazole (an active ingredient in stomach medicine)—which would previously have caused MOF crystal degradation. Thanks to the high stability of APF-80, the structures of the compounds could be observed with clarity. The method also succeeded in directly revealing the shapes of compounds whose structures had not been determined before. Remarkably, it can even distinguish between two closely similar molecules, quinine (a component used to treat malaria) and quinidine (a component used to treat arrhythmia). In other words, it has become possible to capture subtle molecular differences, much like identifying fingerprints.

What’s next

Advancing this technology will significantly accelerate pharmaceutical research. Because it enables structural analysis from only minute amounts of material, it can support faster and more accurate characterization of natural products and novel drug candidates. Moreover, “molecule-encapsulating crystals” like APF-80 are expected to find applications beyond pharmaceuticals, including fragrance compounds, catalysts, and even energy-related materials.

As a new method for more clearly depicting molecular structures that were previously out of reach, this achievement greatly expands future possibilities in the molecular world.

Comment from the researcher

A crystalline sponge is like building a small “photography studio” in the molecular world—one that has been difficult to observe until now. With APF-80, even challenging molecules that could not previously be analyzed can now be captured more clearly. Through further research, we will elucidate the structures of many more compounds and contribute to a wide range of research.

(Yuki Wada: Assistant Professor, Department of Chemistry, School of Science, Institute of Science Tokyo / Director, TEKMOF Inc.)

“Seeing is believing”—the crystalline sponge method is a way to make that saying real. APF-80 has made it possible to observe compounds that could not be analyzed before. I believe it will grow into a powerful crystalline tool that supports emerging drug discovery and materials research. Through TEKMOF, a spin-off from Science Tokyo, we are exploring this research with the goal of social implementation across multiple industries.

(Masaki Kawano: Professor, Department of Chemistry, School of Science, Institute of Science Tokyo / CSO, TEKMOF Inc.)

Professor Kawano (far left) and Assistant Professor Wada (far right)

Dive deeper

Contact

- Remarks

- Research Support Service Desk